《巴黎评论》“作家访谈”余华(英文全文)

原文:https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/8029/the-art-of-fiction-no-261-yu-hua

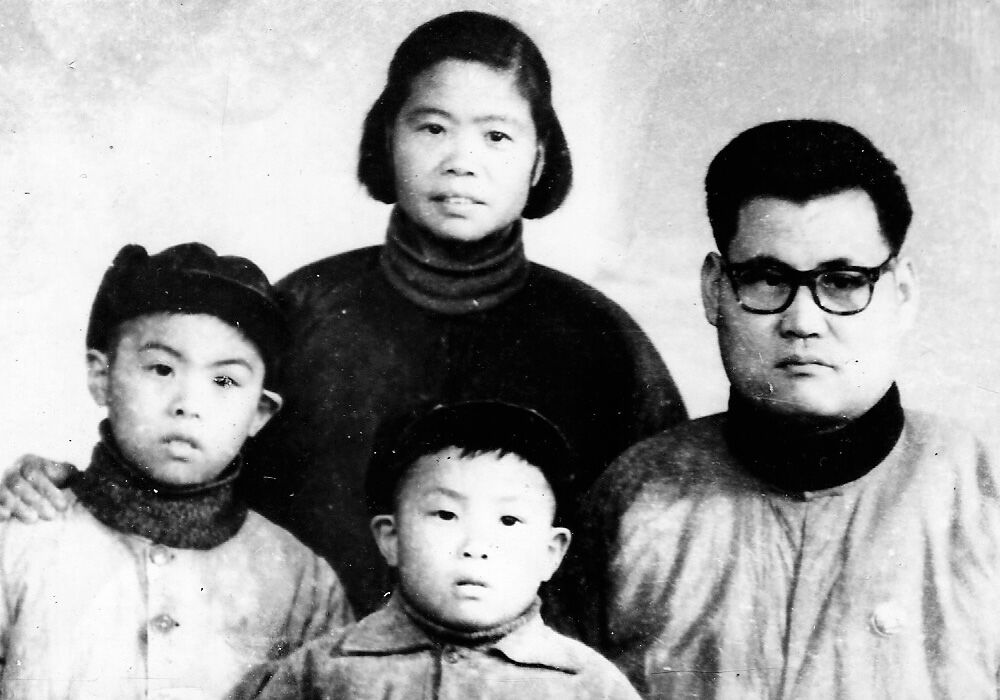

Yu Hua was born in 1960. He grew up in Haiyan County in the Zhejiang province of eastern China, at the height of the Cultural Revolution. His parents were both in the medical profession—his father a surgeon, his mother a nurse—and Yu would often sneak into the hospital where they worked, sometimes napping on the nearby morgue's cool concrete slabs on hot summer days. As a young man, he worked as a dentist for several years and began writing short fiction that drew upon his early exposure to sickness and violence. His landmark stories of the eighties, including "On the Road at Eighteen," established him, alongside Mo Yan, Su Tong, Ge Fei, Ma Yuan, and Can Xue, as one of the leading voices of China's avant-garde literary movement.

In the nineties, Yu Hua turned to long-form fiction, publishing a string of realist novels that merged elements of his early absurdist style with expansive, emotionally fulsome storytelling. Cries in the Drizzle (1992, translation 2007), To Live (1993, 2003), and Chronicle of a Blood Merchant (1995, 2003) marked a new engagement with the upheavals of twentieth-century Chinese history. To Live—which narrates the nearly unimaginable personal loss and suffering of the Chinese Civil War, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution through the tragic figure of the wealthy scion turned peasant farmer Fugui—brought him his most significant audience to date, its success bolstered by Zhang Yimou's award-winning film adaptation.

Once an edgy experimentalist adored by college students, Yu Hua is now one of China's best-selling writers. Each new novel has been an event: Brothers (2005-2006, 2009) is a sprawling black comedy satirizing the political chaos of the Cultural Revolution and the unbridled consumerism and greed of the economic reform era under Deng Xiaoping; the magic realist farce The Seventh Day (2013, 2015) is narrated by a man wandering the living world after his death; and his most recent, Wen cheng (The lost city, 2021), reaches back to the late days of the Qing dynasty. He is also one of the country's best-known public intellectuals, having authored nonfiction books on topics including Western classical music, his creative process, and Chinese culture and politics. His New York Times column, which ran from 2013 to 2014, and China in Ten Words (2010, 2011) have been heralded as some of the most insightful writings on contemporary Chinese society.

More than a quarter century ago, I, then a college senior, reached out to Yu Hua to seek permission to translate To Live into English. Our initial correspondences were via fax machine, and I can still remember the excitement I felt when I received the message agreeing to let me work on his novel. We later exchanged letters, then emails; these days, we communicate almost exclusively on the ubiquitous Chinese "everything app," WeChat.

Our first face-to-face meeting was in New York, around 1998. It was Yu Hua's first trip to the city, and he responded to the neon lights in Times Square, attending his first Broadway show, and visiting a jazz club in the West Village with almost childlike excitement. He exuded a playfulness, a sharp wit, and an irreverent attitude that I found startling. Could this exuberant tourist really be the same person who wrote the harrowing To Live? Apparently so.

Our interviews for The Paris Review were conducted over Zoom earlier this year. I saw glimpses of the same quick humor, biting sarcasm, and disarming honesty I remembered from our time together twenty-five years before, but with new layers of wisdom and reflection.

—Michael Berry

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about being a dentist. How did that come about?

YU HUA

I'd finished high school in 1977, just after the end of the Cultural Revolution, when university entrance exams had been reinstated. I failed, twice, and the third year, there was English on the test, so I had no hope of passing. I gave up and went straight into pulling teeth. At the time, jobs were allocated by the state, and they had me take after my parents, who both worked in our county hospital. I did it for five years, treating mostly farmers.

INTERVIEWER

Did you like it?

YU

Oh, I truly disliked it. We had an eight-hour workday, and you could only take Sundays off. At training school, they had us memorize the veins, the muscles—but there was no reason to know any of that. You really don't have to know much to pull teeth.

INTERVIEWER

When did you start writing short stories?

YU

In 1981 or 1982. I found myself envying people who worked for what we called the cultural center and spent all day loafing around on the streets. I would ask them, "How come you don't have to go to work?" and they would say, "Being out here is our work." I thought, This must be the job for me.

Transferring from the dental hospital was quite difficult, bureaucratically—you had to go through a health bureau, a cultural bureau, and, in the middle, a personnel bureau—but then, of course, there was the even more pressing issue of providing proof that I was qualified. Everyone working there could compose music, paint, or do something else creative, but those things seemed too difficult. There was only one option that looked relatively easy—learning how to write stories. I'd heard that if you'd published one, you could be transferred.

INTERVIEWER

Was it as easy as you'd hoped?

YU

I distinctly remember that writing my first story was extremely painful. I was twenty-one or twenty-two but barely knew how to break a paragraph, where to put a quotation mark. In school, most of our writing practice had been copying denunciations out of the newspaper—the only exercise that was guaranteed to be safe, because if you wrote something yourself and said the wrong thing, then what? You might've been labeled a counterrevolutionary.

On top of that, I could write only at night, and I was living in a one-room house on the edge of my parents' lot, next to a small river. The winter in Haiyan was very cold, and back then there weren't any bathrooms in people's houses—you'd have to walk five, six minutes to find a public toilet. Fortunately, when everyone else was asleep, I could run down to the water by myself and pee into the river. Still, by the time I was too tired to keep writing, both my feet would be numb and my left hand would be freezing. When I rubbed my hands together, it felt like they belonged to two different people---one living and the other dead.

INTERVIEWER

How did you learn how to tell a story?

YU

Yasunari Kawabata was my first teacher. I subscribed to two excellent magazines, Beijing's Shijie wenxue (World literature) and Shanghai's Waiguo wenyi (Foreign art and literature), and I ended up discovering many writers that way, and a lot of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Japanese literature. By then we had a small bookstore in Haiyan, and I would order books almost blindly. One day, I came across a quote by Bernard Berenson, about The Old Man and the Sea and how "every real work of art exhales symbols and allegories"—that's how I knew, when I saw Hemingway's name in the store's catalogue, to ask for a copy.

At the time, when books went out of print the Chinese publishing houses usually just wouldn't put out any more, so you never knew, when you saw a copy of something, if you'd have another chance. I remember persuading a friend who ended up going into the real estate business to swap me Kafka's Selected Stories for War and Peace—he calculated that it was a good deal to get four times the amount of book for the price of one. I read "A Country Doctor" first. The horses in the story appear out of nowhere, come when the doctor says come and leave when he says go. Oh, to summon something and have it appear, to send it away and have it vanish—Kafka taught me that kind of freedom.

But my earliest stories were about the life and the world that I knew, and they haven't been collected, because I've always thought of them as juvenilia. When I first started writing, I had to lay one of those magazines down beside me on the table—otherwise I wouldn't have known how to do it. My first story was bad, hopeless, but there were one or two lines that I thought I'd written, actually, quite well. I was astonished, really, to find myself capable of producing such good sentences. That was enough to give me the confidence to keep going. The second was more successful—it had a narrative, a complete arc. In the third, I found that there wasn't just a story but the beginnings of characters. That story—"Diyi sushe" (Dormitory no. 1), about sharing a room with four or five other dentists training at Ningbo Hospital No. 2—I sent out, and it became my first publication, in a magazine called Xi Hu (West Lake), in 1983. The next year, I was transferred to the cultural center.

INTERVIEWER

Did you find it easy to get published?

YU

I had good luck. During the Cultural Revolution, there’d been no real literary magazines in China—there was one in Shanghai,Zhaoxia (Clouds of dawn), that sort of qualified, though it was all very politically correct—but afterward, the old journals started publishing again, and new ones were founded. Even in Haiyan we had little kiosks that sold nothing but literary magazines, and there was a period from 1978 to 1984 or so when they didn’t have enoughwork by established writers to fill their pages. That created a wonderful environment where editors took unsolicited submissions very seriously—the one good story they found would get passedaround the entire staff.

By 1985, it was different—it became very difficult to get published if you didn’t have a connection, especially if you were considered “avant-garde.” I remember going back to one of these magazine’s offices, sitting around and chatting with some editors, and seeing a hill of submissions piled in the corner, ready for whoever took the trash out to remove them. I realized that if I’d taken another two or three years to start writing, I’d still be a dentist.

INTERVIEWER

Was life at the cultural center as leisurely as it had seemed?

YU

Absolutely. It was very easy to say you had to leave the office to do fieldwork for some project but actually go home and sleep. After I woke up, I’d continue my writing at home. The best thing about being a writer is that you don’t need an alarm clock— a life full of alarm clocks going off all the time is unnecessarily painful.

At first, I’d go into the office every afternoon and, you know, have a look around, but soon that became once a week, and eventually I showed up only on payday, to pick up my salary in cash. Sometimes other employees would complain about me not coming in to work, but it was obvious to my supervisor how little value I’d have brought had I been working there full-time. He just wanted me to write. He’d seen so much—the world was transparent to him. He knew all the Communist Party cadres and he thought, What bores. As I got more of a name, there were fewer complaints.

INTERVIEWER

The eighties were a unique period in Chinese history, a kind of renaissance after the Cultural Revolution. What was your experience of those early days of economic reform?

YU

The avant-garde writers of my generation probably feel the most nostalgia for the eighties. It was in that wave of liberation movements that we started to rethink everything—all the disasters of the sixties and seventies—and to develop a new understanding of how Maoism had suppressed our intellectual lives. Western art and ideologies started flooding in, and we were flocking to throw away our traditional garb and wear showy foreign clothes, whetheror not they fit. But it was a rocky time—sympathies leaned to the left one moment and to the right the next. From 1982 on, we had a very liberal general secretary, Hu Yaobang, but in ’87 a campaign against “spiritual pollution” and “bourgeois liberalization” began and pushed him to resign, just as three of my novellas—“1986,” “Hebian de cuowu” (Mistake by the river), and “The April 3rdIncident”—were about to be published. Suddenly my work was seenas bourgeois, just because it was influenced by Western modernism. I felt like I’d crawled out of a black hole only to be kicked right back in. It turned out that under Zhao Ziyang things would become even more liberalized than before, and those stories would be published by two very good magazines, Shouhuo (Harvest) and Zhongshan(Zhongshan Literary Bimonthly)—but two years later, after the June Fourth Incident, I thought maybe my writing career was over again. No one could have guessed that, with Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992, everything would become even more liberal. The eighties was a very beautiful decade, but its beauty wasn’t linear. For me it was a period of constantly walking back and forth between hope anddespair.

INTERVIEWER

Did you feel a part of a literary movement?

YU

If Mo Yan, Ma Yuan, and Can Xue hadn’t come before me, and if I hadn’t had Su Tong and Ge Fei as peers, I might not have been able to publish very much at all. I’d felt like I was fighting a lonely battle against dogma, but when I read their stories I knew I had comrades in arms. Together, we had the attention of the whole literary world. I remember the editor in chief of one magazine saying publicly that what we were writing wasn’t literature, but a group of critics who were about our age emerged around the same time as us—Chen Xiaoming, Zhang Qing hua, and others—and they were our staunch supporters, and friends.

INTERVIEWER

Did you often come into conflict with editors? You’ve said that, when you were publishing one of your first short stories, the editor found the ending too depressing and asked you to change it.

YU

Of course they asked me to change the ending—it was Beijing wenxue (Beijing literature), in 1983. It was one of their editors, in fact, Li Tuo, who later recommended “1986” and “The April 3rd Incident” to Shouhuo magazine—“1986” in particular was a rather violent story that other magazines were afraid to publish, but not Shou huo. Back then, the editor in chief, Ba Jin, was respected so highly that even the big political families couldn’t do anything to him, and I consider my discussions at Shouhuo to be the moments in which I’ve improved most as a writer. My editor, Xiao Yuanmin, wrote me a very long letter in a thick envelope to say that they’d accepted both novellas, and that there were some parts of “1986” she wanted to tone down while retaining my style. She’d copied out every passage and included her edits underneath, for approval. I was very surprised that this revered magazine treated its lesser-known authors with such respect.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think there’s so much violence in your work from the eighties?

YU

The violence just poured out every time I sat down to write—I couldn’t help it. My early critics would say I was obsessed with violence, and they were right. I think it might have had something to do with my childhood, growing up during the Cultural Revolution. I would see people getting bloodied with sticks and beaten to death in the streets, getting pushed off three-story buildings. Meanwhile, my father was the only surgeon in our county hospital, and my brother and I would often sneak in and watch him in the operating room until he noticed us and told us to get lost. There was a pond next to the operating room, and that’s where the nurses would empty buckets of the tumors they’d cut out of patients. In summer it would be so teeming with flies you couldn’t see the water—like there was a wool blanket covering it. That pond had the most awful stench.

INTERVIEWER

What was your understanding of the Cultural Revolution as a child?

YU

My main impression was of chaos—it was tragic, comic, everything. I was a very nervous child, so anytime there was a fight I’d go and hide, while my brother would always be running ahead, getting very near to the fray. I knew that even if the adults on the street were brandishing knives at one another they wouldn’t hurt us, but from the time I was in elementary school, I always felt a sense of terror. Friends’ parents disappearing, running away, committing suicide—those things are hard to forget.

Dazibao—handwritten “big-character” posters—were everywhere you looked, and in the early period they were quite dull, just covered in revolutionary slogans, but later, they became vehicles for personal attacks—“If you put up a poster about me, I’ll put one up about you.” I think it was reading dazibao that first gave me an idea of how ugly human nature could be. Most of them were about people having affairs, and probably most of them were false. Those were also the first depictions of sex I ever read, and every day after school I would go see if there were any new sex scenes.

Walking outside one afternoon and seeing posters about my father—that was terrifying. Doctors were considered intellectuals, and so he was subject to public denunciation, even though he was a low-level Party official and had served in the People’s Liberation Army during the civil war. The Red Guards tried to arrest him, but he was able to hide in the house of a farmer he’d treated for appendicitis. He ended up being sheltered for over a year by different farmers who were his patients. I very clearly remember hearing news of his moving from one village to another. Toward the end of the Cultural Revolution, after my father came back, he started managing the hospital’s outpatient surgery department, and he requested a bicycle. Every Sunday, if no surgeries were scheduled, he would ride that bicycle to the villages to see those farmers. My brother or I would join him on these trips, which were usually to see people in recovery from their surgeries. I’d sit on the backseat one week, and my brother would sit on it the next.

INTERVIEWER

Did you ever talk about politics at home?

YU

There was no politics, at home, at school, anywhere, other than praising Chairman Mao.

INTERVIEWER

Were there any books in the house? What did you read when you were young?

YU

Apart from the Selected Works of Mao Zedong, all we had were books about medicine. My elementary- and middle-school reading was Lu Xun, no one else, so naturally I didn’t like him one bit back then, though these days I imagine we’d have a good laugh together. In the later days of the Cultural Revolution, the library in town reopened, with maybe thirty or forty volumes of what they called revolutionary literature, the sanctioned kind, and I read all of that in one summer. But there were a small number of novels that got passed around my middle school in secret, until they lost their front or back covers. There’d be ten pages missing from the beginning and another ten missing from the end. By the time they reached me, I’d have no idea even what their titles or who their authors were. In my experience, you can live with not knowing how a story begins, but not knowing how it ends? Now that’s torture. I found it so unbearable that I started making them up myself, inventing one ending after another. My classmates would crowd around asking to hear my stories. When I think back to it now,I realize that’s where my writing career began.

INTERVIEWER

Have you been influenced by the generation of Chinese authors that came before yours?

YU

When I started writing, contemporary Chinese literature was still mostly scar literature, a movement expressing outrage at the Cultural Revolution. I was interested in Wang Zengqi because he dealt with emotional pain in a way that seemed unique. I’d read his stories “Buddhist Initiation” and “A Tale of Big Nur” in 1980 and thought that they were very good. The best among that generation had a special thing in common, which was that they treated encouraging younger writers as part of the order of things. Conversely, the second- or third-rate writers of the time treated my generation very badly, as if we were threatening to take their place.

The writer with whom I was most infatuated, though, was Kawabata. I read a story of his called “The Dancing Girl of Izu,” and I was enamored with him for four years, reading everything I could get my hands on—Thousand Cranes, The Old Capital, Snow Country, which I still think is just the best . . . Kawabata taught me that it’s detail, not plot, that makes something worth reading—that great works of literature aren’t sequences of events but assemblages of unforgettable details. That’s what readers find moving—the storyline is merely interesting. At twenty-one, I was completely sunk by one of his stories. A woman whose fiancé is at war worries he’s died in battle, visits a house that’s under construction in his neighborhood, and speculates about who will livethere when it’s complete. This is classic Kawabata, and it becamemy ideal—a story without a protagonist, just supporting characters. He showed me that you didn’t have to write in this constricted narrative progression of life unto death, that you could reverse it.

INTERVIEWER

Cries in the Drizzle is a novel about memory, with a narrative that weaves together various different timelines. How did you come to that structure?

YU

I realized that time is ordered differently in memory than reality—it’s not linear. When we think about the past, often the first thing we’ll remember is something from ten years ago, and that’ll remind us of something from five years ago, which will remind us of something two years before that. That allowed me to write about characters and events that didn’t relate to one another directly, to construct three layers of experience—the narrator, his brothers, and his classmates are part of my generation, born in the sixties, but there’s also my father’s generation and my grandfather’s. I was trying to write about the social makeup of the time—I’d gone to Beijing to get my degree in literature, because after a few years the cultural center decided that having a diploma was very important, and I started Cries while I was there. My class was ’88 to ’91, and during the 1989 protests I’d ride to Tiananmen Square almost every day on this old bike that was so battered every part of it rang except the bell. I remember there was such fervor that everyone who went up to speak was hoarse. They’d go on even if they’d lost their voices.

INTERVIEWER

What was it like to finally be at university?

YU

There was a lot of dropping in here and there to play mah-jongg— there was very little schoolwork, and we basically didn’t have class, either. Mo Yan and I shared a room for two years, and one semes ter, he mingled a bit at orientation, then disappeared. The man was gone. He’d gone back to Gaomi, in Shandong, to build a house. By the time he came back, the semester was almost over, but no one had noticed a thing.

INTERVIEWER

How was it sharing a room with Mo Yan? Did you show each other your work?

YU

While I was writing Cries in the Drizzle, he was writing The Republic of Wine. We rarely exchanged our works in progress, but we worked side by side, at two desks that faced the same wall. At first, there was just one cabinet in the room to divide our separate spaces, and later we went and stole another, which he had discovered somewhere. When we opened their doors, they divided the room almost completely. But the thing is, when you’re writing longhand, you want to lean back, to look to the right or the left as you’re thinking, and there was a small gap between the two cabinets. Often I’d look over and see he’d be looking at me. It felt wrong. I’d say,“You’re affecting my work.” He’d say, “You’re affecting my work.” In the end he went to some garbage pile and found an old calendar with photos of popular actors. He hung it on a nail—the gap wassealed.

INTERVIEWER

Was writing novels much different from stories?

YU

I always felt that writing short stories was more of a job. I could complete them on a schedule—they were inevitably finished within a day, or a few. Novels are impossible to execute that way. Over the years that you work, your sense of the book shifts. You deepen your understanding of your characters—you’re living together. Once I’m halfway done with a novel, they start saying things of their own accord. Sometimes I’ll think to myself, This is even better than I could have imagined.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve said that writing splits your life in two.

YU

Yes, you live one life of invention and another in reality. As the first grows, the second shrinks—there’s no way around it. The more you write, the bigger this imagined world gets. And the other life stays on the chair, quiet, where the body is still.

Or maybe your feet move. You know, Mo Yan, he has a terrible habit—when he enters the depths, his foot goes like this.

INTERVIEWER

Did you complain?

YU

There were times I thought about it, but I knew what it meant. When things are going well, you might find yourself emitting some funny noises. It bothered him that I would tap my hand on the table—he’d call me a bastard later, but when it was happening, he kept quiet too. You can develop a respect so deep that you resist making a noise even when you get up to go to the bathroom. You don’t want to disturb the other’s beautiful state of concentration.

INTERVIEWER

How does a novel begin for you?

YU

Sometimes the first thing to emerge is a character. Chronicle of a Blood Merchant came about because one day in the early nineties, my wife and I were walking on Wangfujing Street in the winter when we saw a man with his coat flapping open walking toward us, sobbing uncontrollably. It’s unusual to see someone sobbing like that in public, on Beijing’s biggest shopping street. The image wouldn’t leave my mind, and it made me think of the farmers who would come to the hospital to sell blood when I was a child. I imagined that this man had gotten so old that nobody wanted to buy his blood anymore—that this was the reason he was crying.

Other times, there’s just a feeling. When I started The Seventh Day, I planned to write a book—a short one, not like Brothers—in which I could explore all the absurdities of life in China today. I wanted it to be a monument of our society in the distant future, the way when you’re showing someone around a city, you tell them to meet you at an iconic landmark. Finally, a very simple idea materialized—someone has died, and the funeral home calls him to say, You’re late. After that, it sort of all came out at once.

INTERVIEWER

How about To Live?

YU

Well, I’d long hoped to write about a Chinese person and their fate through the ups and downs of the twentieth century. After the 1911 Revolution, we never had a moment’s peace for decades—first there was infighting between military warlords and there were bandits everywhere, later we fought in the Second Sino-Japanese War, then the civil war started up again, and after that there were plagues and famines—but I didn’t know how to write about any of it until one day the title To Live leapt out at me aftera midday nap. It sounded great in Chinese. And I had the figure of Fugui, a farmer whose face was covered in wrinkles caked with dirt.

INTERVIEWER

Your work has gone through many phases—avant-garde, historical, satirical . . . How would you define your style, or voice?

YU

A writer’s voice doesn’t yet exist when a story is being conceived—only in the actual writing does it jump out, because a writer is always looking for breakthroughs. My story “On the Road at Eighteen” was my first breakthrough moment—when I realized that I could write, like Kafka, without forcing the narrative logic to subscribe to the logic of real life. Up through Cries in the Drizzle, I was using a kind of modernist style in my writing, and during this stage I was sort of just playing around with words, looking for ways to get language to bend to the things that I wanted to write about.

When I started To Live I was still writing in that kind of style, but after I’d written ten thousand words I still didn’t feel it was right. The earliest draft was in the third person, but eventually I realized that if you look at Fugui from the outside, there doesn’t seem to be anything in his life but tragedy. I needed to let him narrate his ownstory, and I had to use only the simplest language and the most common figures of speech—he’s a farmer, not an intellectual! It was the second time I felt that kind of breakthrough, discovering that I could use the plainest language possible to create a vivid story. That allowed me to see that I could have an infinite variety of stylistic selves. What I found was that when Fugui was narrating even his own suffering, he could do so in a way that was joyous—and to live is to narrateone’s experience of suffering joyously.

INTERVIEWER

There’s another narrator in the book—the folk song collector. What made you add him in?

YU

After I’d finished the new draft in first person, I still felt like there was something missing. I’d had Fugui tell his own story, but who was his audience? To recount a life like his, you need a listener who’s extremely patient, and a bit detached. I came up with the folk song collector—and, to an extent, Fugui himself—by drawing on my own experiences. In 1983, when I was working for the cultural center, they’d sent me down to the countryside to collect folktales, proverbs, and songs—what we called the three great inheritances. It was the only real work I ever did while I was there. I was the youngest employee, so they kept me there all summer. I’d go around in my sandals, wearing a straw hat, carrying a big thermos everywhere, hanging out on the edges of the fields so that when I ran out of water I could fill it up with the tea the farmers were always drinking.

At one point I was researching a specific song, and I went to a small village to ask who I should consult. They suggested that I go to an even smaller village to find an old man whose wife and children had passed away. When I found him, he was plowing and talking seemingly to himself. He was ecstatic when I asked him to sing for me, and I had to ask him to slow down—my job was to write down the lyrics, and the person responsible for melodies was coming in a few days. He told me that the names he’d been calling as he worked belonged to his dead wife and sons, and that it was his ox he was talking to, telling him about his family. It moved me so much. The frame of the song collector was also a matter of pacing—it’s such a sad story that sometimes the reader needs to pause for a minute.

INTERVIEWER

Did you do much research otherwise?

YU

I didn’t need to consult any documents. Fugui is part of my grandfather’s generation, but I felt like I was living in his world. China only really began developing in the eighties—the house I’d grown up in, the table we used, the beds we slept in, were all built before liberation. The highway we’d take to visit my mother’s parents every new year in Shaoxing was the same one that had been built by the Japanese when they colonized China. When I would go to my friends’ homes to play, their grandfathers were Fugui or Xu Sanguan. I very much understood them.

When I wrote about the Huaihai campaign during the civil war—the screaming and crying and the great field of blood, how the wounded were tossed into a pile and the next day it was silent because everybody had frozen to death—that was all drawn from what my father had told me about his time as a Nationalist soldier. He was captured and taken prisoner in that battle. You can’t imagine the hunger—they’d been encircled for such a longtime. He thought the Communist Party was amazing because the Liberation Army guys gave him steamed buns to eat, brought him water to drink. Unlike Fugui, he didn’t have a home to go back to, so he decided to join the PLA and fight with them all the way.

INTERVIEWER

Did the writing come easily? Were there many drafts?

YU

Overall, it took a year, more or less. I used to write by hand, and I’d leave a draft alone for a month or two, edit it, set it aside for another month or two, then edit it again. Usually by the time a second draft is done, I’ve mostly figured out how it’s going to go. But while I was editing—oh, the tears . . . Only when you read the whole book in one pass do you understand the potency of it. Back then we didn’t have tissues, and in the end what I had to do was wrap a towel around one of my hands, wiping my face with it and writing with the other.

INTERVIEWER

Do you often cry when you write?

YU

I think if a writer can’t even move themselves they probably won’t move their readers. I remember when I was writing Brothers I was crying so hard—snot and everything—that my wife would come in and see a mountain of used tissues next to me. We did have tissues by then.

INTERVIEWER

But those books are quite funny, too.

YU

To Live needed some humor because otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to keep going. I’ve heard that it’s tough reading—Zhang Yimou, who directed the film adaptation, told me that viewers wouldn’t be able to take it, but really it’s the writer who can’t!

INTERVIEWER

What did you think of the film’s happier ending?

YU

I love the movie. Only an idiot would have been faithful to the original—idiots have no ideas of their own, all they can do is scour the source material.

I’ve never seen the TV series, by the way. It’s too long. TV just goes on and on, I can’t stand it.

INTERVIEWER

Did you imagine the book would become a contemporary classic?

YU

With To Live as a title, the book has no intention of ever dying! But my greatest wish was for Shouhuo to serialize it and put it at the very top of the table of contents, which they eventually did. I never could have imagined it would sell so well—I’ve heard it’s sold as many as twenty million copies in China, not including audiobooks, ebooks, or pirated copies. My publisher told me I must have sold at least fifty million pirated copies.

The English edition of To Live has also done quite well. You should be getting biannual royalties now, yes?

INTERVIEWER

No. So far they haven’t given me a penny.

YU

Surely you should get something!

INTERVIEWER

I’ll look into it. Does it bother you that your books have been pirated?

YU

I have no objections. All the movies I watch are pirated—to all the filmmakers out there, my apologies, but the kinds I like don’t screen in our theaters, so it’s the only way I can watch them! Our pirating technologies are incredible, by the way. Cannes Film Festival ends in May, and by August or September we can watch the movies, with translated subtitles.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about how you came to be published in the States.

YU

Li Tuo helped publicize my work at American universities after he moved to the U.S. to teach—that’s how my first translator, Andrew F. Jones, learned about me, while he was teaching at Berkeley. But it wasn’t easy going until Ha Jin recommended my books to his editor at Anchor, LuAnn Walther. There were almost no American publishers who knew how to introduce a Chinese writer to their readers, but LuAnn could do it because HaJin had been such a success for her. He’d won the National BookAward.

INTERVIEWER

Didn’t you live in Iowa for a time, when you were writing Brothers?

YU

I was invited to Iowa in 2003, after To Live and Chronicle of a Blood Merchant were published in English. I’d written the beginning of Brothers, but I didn’t write at all while I was there—there wasn’t any way to do it in an environment like that. In Iowa, everyday life was just . . . eating. Su Tong had decided he was going to move out there to write, and then, well, he wrote one short story. He became an alcoholic—he went to the Drinkers’ Workshop. Mo Yan went, too, thinking he was going to stay for a while, and came back in ten days. It’s just too small. To be fair, if my wife and son hadn’t joined me, I probably would have left sooner, too.

It’s funny—they kept telling us that Iowa was the literary capital of America. Then, when my family and I went on a trip to visit maybe twenty colleges across the States, we got to Minneapolis, maybe five or six hours away from Iowa, and the people there said to us, “Minneapolis is the literary capital of America.” When we got to New York, no one said anything.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever considered emigrating?

YU

No. I’m too used to life in China, and you can’t find the bustle of Beijing anywhere else. Not to mention that I don’t speak any foreign languages. I remember, back in the nineties, Wang Shuo went to the U.S. for a year. We all thought, Wow, his English must begetting so good, but it turned out he still couldn’t speak it. ZhangYuan told me he’d been to LA to visit him—they’d gotten coffee on Wang Shuo’s street and managed to sit there all day without hearing a word of English. Everyone was Chinese. If I moved to the U.S., my life would probably be like Wang Shuo’s was that year. If that’s the case, I might as well stay in Beijing.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve never been concerned about facing repercussions for your writing? Your column for the New York Times, say, didn’t cause you any trouble with officials in Beijing?

YU

“Officially,” they don’t know about it. To this day, nobody has approached me about the articles I’ve published in the U.S. We have lots of excellent people in government today—some of them have told me they’ve read the interviews I’ve given abroad and thought everything I said was right, even though they couldn’t endorse it publicly. It’s possible some have seen my column but let bygones be bygones. Before I leave the country, my father always calls me up and says, “You’re not to say anything critical about the Communist Party, okay?” He has no idea what’s in the articles I wrote—if he did, he wouldn’t be able to sleep.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think about your reader as you write?

YU

It would be impossible—China is such a sweeping country, with such a diversity of cultures. You can’t know what these different kinds of people might want. I mean, if you’re expecting only two people to read your book, then sure, you can call both of them upand ask. But if there are twenty thousand? All sorts of disagreements and confusions can arise. I remember that one reader complained about the way I described raising lambs in To Live. He thought the book was inaccurate because, where he came from, the sheep roam freely. Sure, in the northwest this is the case, but not in the south. There’s really no way to avoid this kind of misunderstanding.

When you’re writing, you are always thinking of the reader, but that reader ultimately has to be yourself. If you discover, Wait, this sentence isn’t quite right, that’s the reader in you, the part of you whose taste has been shaped by hundreds of great works ofliterature, speaking up. A writer who’s always reading the best—whatever they come up with can’t be that bad. But someone who’s just reading crap, no matter how talented they are, won’t get anywhere good. And sometimes the reader and the writer in you will argue. The writer thinks, It’s fine the way it is! But the reader says, No, it’s still not quite there! Most of the time, the writer has a nap and realizes, Wait, actually, they might’ve had a point there . . .

INTERVIEWER

What about early readers? Do you have a friend or editor you send everything to?

YU

One problem I’ve found is that as a writer gets famous, their editors become afraid of making suggestions. Before Wen cheng was published, all they did was pick out some typos and ask me if I agreed to their edits. If they need my consent to correct my spelling and punctuation, then of course they’ll never get around to changing anything else. These days, my wife and son are the only ones who still give me suggestions, because nobody else does. She and I were in the master’s program in creative writing together—she was a poet but she gave that up, because if there were two writers in one household it would be chaos. By the time I wrote The Seventh Day, my kid was twenty, so he could offer some feedback too. Come to think of it, he also read a draft of Brothers when he was in middle school and discovered a typo. I remember some of his classmates told my wife that they’d liked the first volume. I thought, Should kids really be reading this stuff ?

INTERVIEWER

There is quite a lot of sex in Brothers.

YU

It was an important way to express the differences between these two eras—the Cultural Revolution was a time of extreme sexual repression, and the early days of economic reform were a time of not so much sexual openness as sexual frenzy. During the Cultural Revolution, there were loads of men spying on women in bathrooms. Plenty of people who did this don’t want to admit it, so after the book came out, they would say I must have been spying on women in bathrooms back then. I suspect they’re unhappy I’m writing about them, you know?

After economic reform began, some rich men started taking ten wives. I knew one who built a house with seven floors, one wife on each floor—I saw it myself, I knew the guy.

INTERVIEWER

Wow.

YU

This is our reality. Besides, writing about sex is an important tradition in Chinese literature. Think about The Plum in the Golden Vase, which is a great novel. Or The Carnal Prayer Mat.

INTERVIEWER

Brothers is your longest novel. Did you have the structure mapped out before you started?

YU

I hadn’t envisioned it being so long—I thought it might be a hundred thousand words at most. I started the book just after I’d finished Chronicle of a Blood Merchant, but managed only to writethe part on the Cultural Revolution, which ended up being about two hundred thousand words by itself. I didn’t start it back up again until 2003 and I didn’t finish it until 2006. Looking back, I see that if I’d finished Brothers in 1996, it would be a completely different book. The first volume is a tragedy, but a tragedy in which comedy is always just beneath the surface. The second is more decisively a comedy, but it’s laced with tragedy, too.

INTERVIEWER

Do you often get stuck or leave things unfinished?

YU

Right now, I have three unfinished books that are just sitting around. I keep telling myself I’m not allowed to do anything but try and resuscitate those three, but there’s less and less time to do it, and it’s extremely difficult to go searching for, and to recover, the feeling you had when you were in the thick of it. It took me twentyone years to finish Wen cheng.

INTERVIEWER

How did you keep that feeling going?

YU

My notes were extremely important. Of all my books, it’s the one that goes back furthest in history, so I needed to do a lot of historical and literary research. That alone took me maybe two years—I collected lots of great details about daily life that would inspire me and ensure accuracy, even if I didn’t use all the specifics.

INTERVIEWER

What kinds of challenges did the book pose for you?

YU

I really struggled with the female protagonist, Xiao Mei. She’s atragic figure governed by two extremes, tradition and westernization. Her emotional responses and behavioral responses are involuntary—she’s not in control of herself, her fate isn’t in her hands.I thought I understood her while I was writing, I even saw all the reprehensible parts of her as beautiful, but I found myself revising again and again. My wife and son both kept telling me that she was poorly written. My wife finally said, “I don’t think you’re in love with Xiao Mei,” and she was right. I took my time and invested love in her.

The dialogue was a challenge, too, or felt like one at first. I was in Italy one year for the Festivaletteratura in Mantua, just after the Italian translation of The Seventh Day came out and George Saunders had published Lincoln in the Bardo. We’d both been writing about dead people, so we were put together for a conversation. Saunders brought up that he’d agonized over how to render the dialogue, and I told him, “You’ve got nothing to worry about—the people from Lincoln’s time are dead, they’re not going to come back and tell you that you got the language wrong!” But Wen cheng is set in a relatively distant—but not too distant—past. Not only are many children of people of that time still living, but there are many scholars in China who have studied the period extensively, so the language was a problem for meand I had to solve it my own way. I went back and reread Lu Xun,Mao Dun, and Ba Jin, and I realized that modern Chinese grammar was already quite developed by the time they were writing. The vocabulary was different, but I thought archaic terms would sound awkward to the reader. I decided so long as I didn’t use words that sounded distinctly anachronistic, that was good enough.

INTERVIEWER

Why did it take so long to finish the book?

YU

I was going abroad all the time, and I was working on Brothers and The Seventh Day in between. My friends kept telling me I shouldn’t be running around, that I should work on my writing while I was still young and in good health, but I’m someone who likes to have fun. How would I do all this traveling when I got old?

Literature is not the only thing in my life. I encourage my students to think this way, too. Recently, I told one of them, “Let’s meet this afternoon to talk about the story you wrote,” and he said, “Professor, I’m going clubbing tonight.” I said, “All right, have fun.”

Translated from the Chinese with thanks to Muhua Yang